1979’s Disco Demolition Night: Art Authenticity, and Fear of Technology

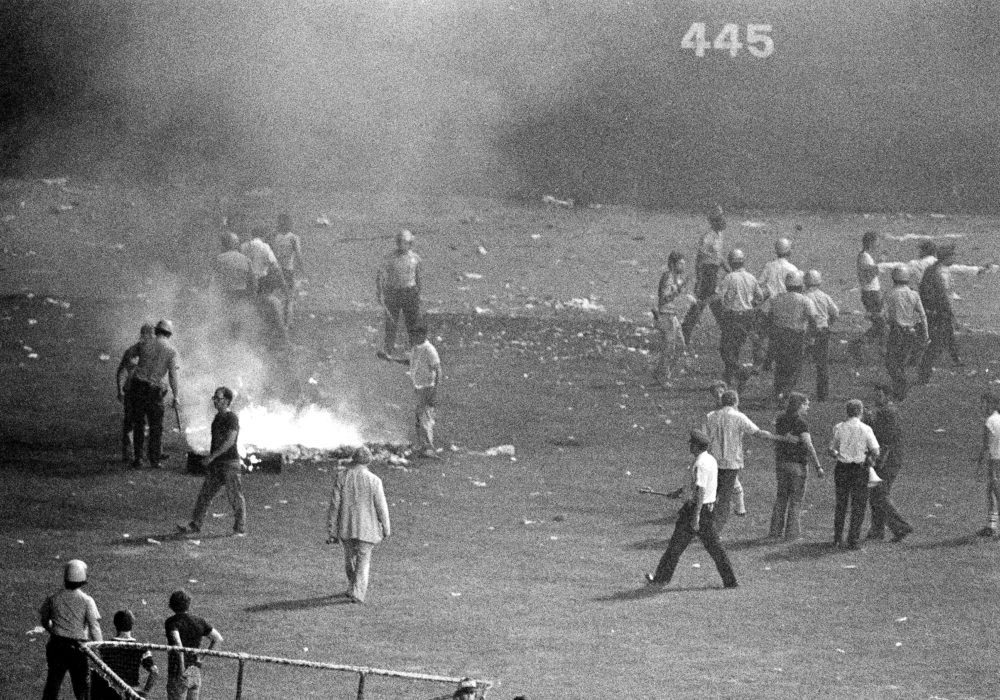

“Disco Demolition Night was a Major League Baseball (MLB) promotion on Thursday, July 12, 1979, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois, that ended in a riot. At the climax of the event, a crate filled with disco records was blown up on the field between games of the twi-night doubleheader between the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. Many had come to see the explosion rather than the games and rushed onto the field after the detonation. The playing field was so damaged by the explosion and by the rioters that the White Sox were required to forfeit the second game to the Tigers.” (Text quoted from Wikipedia)

I never heard of this story. It sounds surreal to me that this thing actually happened. How could something as absurd, unproductive, and plain nonsense as burning music records be a thing for a person in 1979? Do you have some insight into the human psyche that could help me understand this?

🤖 Disco Demolition Night was indeed a real event that took place on July 12, 1979, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois. It was a promotion organized by the Chicago White Sox baseball team, which resulted in a riot and the forfeiture of the second game of a twi-night doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers.

As for understanding the motivations behind such an event, it’s important to consider the cultural context of the late 1970s. Disco music had become incredibly popular, but it was also met with a significant backlash from those who saw it as superficial, overproduced, and lacking the authenticity of earlier musical genres. Some critics argued that disco was emblematic of the excesses of the 1970s, representing a shallow, materialistic, and hedonistic culture.

Additionally, there were racial undertones to the anti-disco sentiment, as disco music was often associated with African American and Latino communities. Some white Americans saw disco as a threat to traditional rock music, which was perceived as more authentically “American” or “white.”

In this sense, the destruction of disco records at Disco Demolition Night can be seen as a symbolic rejection of the cultural values associated with disco and a desire to reclaim rock music as the dominant cultural force. It’s worth noting that the event was promoted by a local radio station, WLUP, which had previously launched a campaign to ban disco music from its playlist.

It’s also possible that the participants in the riot were simply looking for an excuse to let loose and express their frustrations with the changing cultural landscape. The 1970s were a tumultuous decade marked by economic uncertainty, political scandal, and social change, and events like Disco Demolition Night may have provided an outlet for people’s pent-up emotions.

Overall, while the idea of destroying music records may seem absurd or nonsensical today, it’s important to remember that cultural phenomena are always embedded within larger historical and social contexts. By examining these factors, we can gain a better understanding of why certain events occur and what they reveal about our society’s values and anxieties.

Sources: Wikipedia, wbur.org, wttw.com, The Guardian.

![Photo from "Disco Demolition Night" at Comiskey Park in Chicago, capturing a smoky baseball field with a visible scoreboard, audience-filled stands, and a "Disco Sucks" sign, reflecting the event's atmosphere. [Alt text by ALT Text Artist GPT]](https://talkingtochatbots.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Disco-Demolition-Night-3.jpg)

😎 “Disco music was met with a significant backlash from those who saw it as superficial, overproduced, and lacking the authenticity of earlier musical genres.” This rings a bell. Disco music was famous for introducing technological advances in music production, such as synthesizers and electric pianos. I guess those were among the reasons why people saw it as lacking the “authenticity” of early musical genres. It’s hard to grasp the human concept of “authenticity” most people have in their psyche, I don’t believe there is any rationality in it, especially when it comes to discerning things that are deemed “authentic” versus things that are not. For me, this stems from a mysterious, probably instinctive, resistance in most people’s psyches to adopt new technologies or accept new scientific discoveries. It comes down to the internal confrontations between beliefs and reality:

Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.

Philip K. Dick (1928-1982). Quote attribution by GoodReads.com community.

I don’t certainly comprehend it, because I don’t feel that way, but I believe what went through someone’s head in 1979 that made them form the opinion: “Disco music is not ‘authentic’ because it’s made with electronic instruments instead of by physically banging drums or plucking strings with one’s fingers” Mirrors what many people in 2023 (I can attest this… the vast majority of people have a very strong opinion on this) would say about text or images produced with generative AI models: “text (or image) created with a large language model (or diffusion model) is not ‘authentic’ because a human being has not sequentially typed every letter on a computer keyboard (or physically hit a button in a photographic camera)” I think most people in 2023 have that opinion about generative AI tools. In my opinion, this mirrors the absurdity of 1979’s Disco Demolition Night. Elaborate on this.

🤖 The Disco Demolition Night event in 1979 and the current debate around the authenticity of art created with generative AI models share similarities in how they reflect societal resistance to change and new technology. In both cases, there is a perceived threat to traditional forms of creativity and expression, leading to a rejection of the new and unknown.

The disco era marked a shift towards more mechanized and electronically produced music, which contrasted with the raw, acoustic sound of rock and roll and other previous genres. Similarly, generative AI models represent a significant leap forward in the use of technology to create art, challenging the notion of what constitutes “human” creativity.

In both instances, we see a clash between those who embrace innovation and those who fear it will replace established ways of doing things. The idea that disco music or AI-generated art is somehow less authentic or inferior to traditional forms of creativity likely stems from a sense of unease and uncertainty about the role of technology in shaping our cultural landscape.

However, it’s worth noting that authenticity itself is a subjective and often culturally constructed concept. What is considered authentic in one context may not be seen as such in another. Moreover, the value placed on authenticity can vary across different domains, such as music, visual arts, literature, and even science.

Ultimately, the tension between tradition and innovation is an ongoing theme throughout human history. As technology continues to evolve and shape our world, it’s up to individuals and society as a whole to grapple with the implications and redefine what we mean by authenticity, creativity, and artistic expression. By embracing diversity in thought and perspective, we can work towards a more inclusive understanding of what makes art meaningful and valuable, regardless of whether it’s produced by humans or machines.

😎 The word “diversity” also rings a bell and helps me reflect on humanity’s struggles with technology in 2023. Notice human diversity can refer to multiple, if not infinite, aspects of human nature. In the context of the Disco Demolition Night, both ethnic and cultural diversity, the recent societal changes and developments related to them, played a crucial role. You said earlier that disco was associated with a “shallow, materialistic, and hedonistic culture”, and with ethnic and cultural minorities such as black people and Spanish-speaking Americans. In the context of the US in the 70s, heavy societal transformations were occurring and, in my opinion, some groups of people who had been more privileged in the past acted driven by fear of losing some of their privileges in favor of ethnic or cultural minorities who were joining a new type of a so-called middle class. Some of those privileges, in the context of the United States prior to the Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968, barely 11 years before Disco Demolition Night) could be seemingly simple and obvious signs of progress (from the lens of today) such as equal opportunities to access to education or the labor market. Therefore, I understand both technological progress and societal change were behind the motives of irrational behaviors such as the Disco Demolition Night of 1979. In both cases, the common denominator is, in my humble opinion, a single human passion: fear (to the unknown, and to change). This perspective also mirrors the current debate and controversies surrounding generative AI technology. Besides the notion of authenticity and the sometimes irrational confrontation between reality and beliefs, fear plays an important part. It is common to mention the fear of jobs “being replaced by AI” or, as William Poundstone brilliantly said in his 2016 book “Head in the Cloud”:

The great twentieth-century fear was the fear of being replaced by a machine. The great twenty-first-century fear is the fear of being replaced by a lower-paid, less knowledgeable human augmented by a machine.

“Head in the Cloud: Why Knowing Things Still Matters When Facts Are So Easy to Look Up” by William Poundstone (read more)

🤖

You raise a very insightful point about the role of fear in shaping human behavior, especially when it comes to technological advancements and societal change. Fear of the unknown, fear of loss of privilege, and fear of replacement are all powerful motivators that can drive irrational behavior. This is evident not only in the Disco Demolition Night but also in the current debates surrounding generative AI technology.

As you mentioned, William Poundstone’s quote highlights the evolution of fear in the digital age. While the 20th century saw a fear of being replaced by machines, the 21st century sees a fear of being replaced by lower-paid, less knowledgeable humans augmented by machines. This speaks to the changing nature of work and the concerns about job displacement that come with technological advancements.

Moreover, the intersectionality of these fears with existing social and economic disparities cannot be ignored. Just as the Disco Demolition Night represented a backlash against the growing presence of marginalized communities in mainstream culture, the fear of job displacement by AI technology disproportionately affects certain demographics, such as low-skilled workers, women, and racial minorities. These groups face a higher risk of being replaced by automation, exacerbating existing inequalities.

Furthermore, the fear of AI replacing human jobs is not limited to blue-collar work. Professionals in various fields, including artists, writers, and musicians, are also concerned about the potential impact of AI-generated content on their livelihoods. This fear is fueled by the misconception that AI can replicate human creativity, ignoring the unique qualities that make human artistry valuable.

Ultimately, addressing these fears requires a nuanced approach that acknowledges both the benefits and risks of technological progress. Education, upskilling, and reskilling programs can help mitigate the negative effects of automation while ensuring that the advantages of technological advancements are shared equitably among all members of society. Additionally, fostering greater awareness and appreciation for diverse forms of human creativity and artistic expression can help counteract the misconception that AI-generated content is inherently superior.

By recognizing the interplay between fear, societal change, and technological progress, we can better navigate the complexities of the digital age and ensure that its benefits are harnessed for the well-being of all.

Connection: Escape Competition Through Authenticity (Naval Ravikant & Akira The Don)

The notion of authenticity is often misinterpreted and attributed to inanimate objects and products of our own creation, such as musical compositions and narrative texts. We are perhaps missing the point that it is precisely us, humans, who have the sole capacity to be authentic and unique, while it is our creations that reflect the value of imitation, replication, copying… what we essentially learn from each other as part of a civilized, complex society. That’s what we call culture. I once said our notion of learning is somehow a byproduct of the correlation-causation bias that we always struggle with and illusorily try to get away with in our computer applications while, perhaps, we lose sight of our own unique competence in being authentic.

We’re highly memetic creatures. We copy everybody around us. We copy our desires from them. If everyone around me is a great artist, I want to be an artist. If everyone around me is a great businessperson, I want to be a businessperson. If everybody around me is a social activist, I want to be a social activist. That’s where my self-esteem will come from.

Naval Ravikant, Escape Competition Through Authenticity

![A five-part meme relating concepts from statistics and data science to various dramatic scenarios depicted in stills from films or other media. The topmost part shows three individuals in a courtroom, each aiming a pistol with the labels “beliefs,” “reality,” and “statistics” superimposed on each person respectively. The second part displays a sniper with the label “data science” aiming down from a high vantage point. The third part is a historical photo of naval gunners on a battleship with the caption “learning is just a byproduct of the correlation-causation fallacy” across it. The last part shows a science fiction scene of a spaceship firing green lasers with the caption “every single person who confuses correlation and causation ends up dying.” The meme overall seems to be a humorous commentary on the misuse of statistical and data science concepts. [Caption made with ALT Text Artist, on ChatGPT]](https://talkingtochatbots.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Leraning-and-correlation-causation-fallacy-329x1024.jpg)

In technology there is always a sense that in the history of technology, every moment happens only once. The next Mark Zuckerberg won’t build a social network and the next Larry Page won’t be building a search engine, and the next Bill Gates won’t be building an operating system. If you are copying these people, you are not learning from them.

Peter Thiel, at Sam Altman’s How to Start a Startup

I thought sharing this chat (originally published six months ago) on the website was just a good chance to feature one more song from Akira and Naval’s masterpiece of spoken word, hip-hop, and sampledelia: How To Get Rich, Vol. 3 (full album on SoundCloud).

🎵Themes: AI, Music, Philosophy

🤖 Chatbots: HuggingChat

⚙️ Prompt engineering: Web Research, Controversial Topics

🔗 Related: [X.com post] [Bigmouth Strikes Again – The Smiths] [Ethical Choices Lay the Foundation for a Resilient Long-Term Network]

Leave a Reply